More than any other early American, Noah Webster influenced the direction and force of American English. By doing that, he had a great influence on the way that English looks to people around the world who read, write, study, and speak it today.

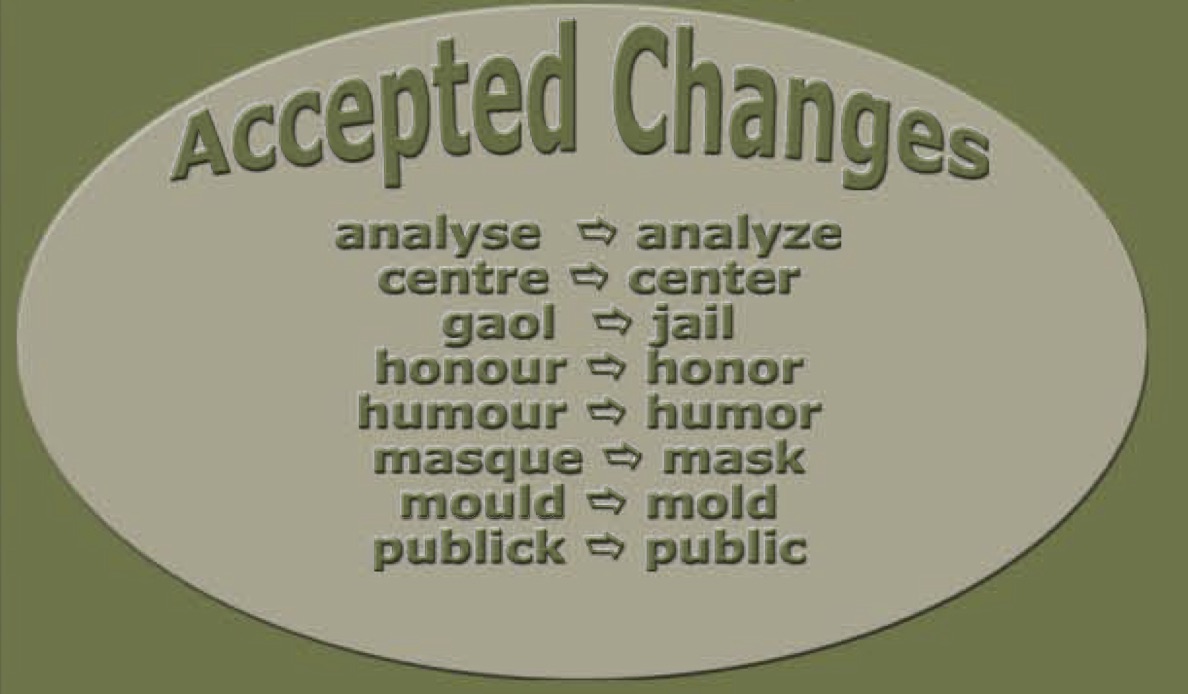

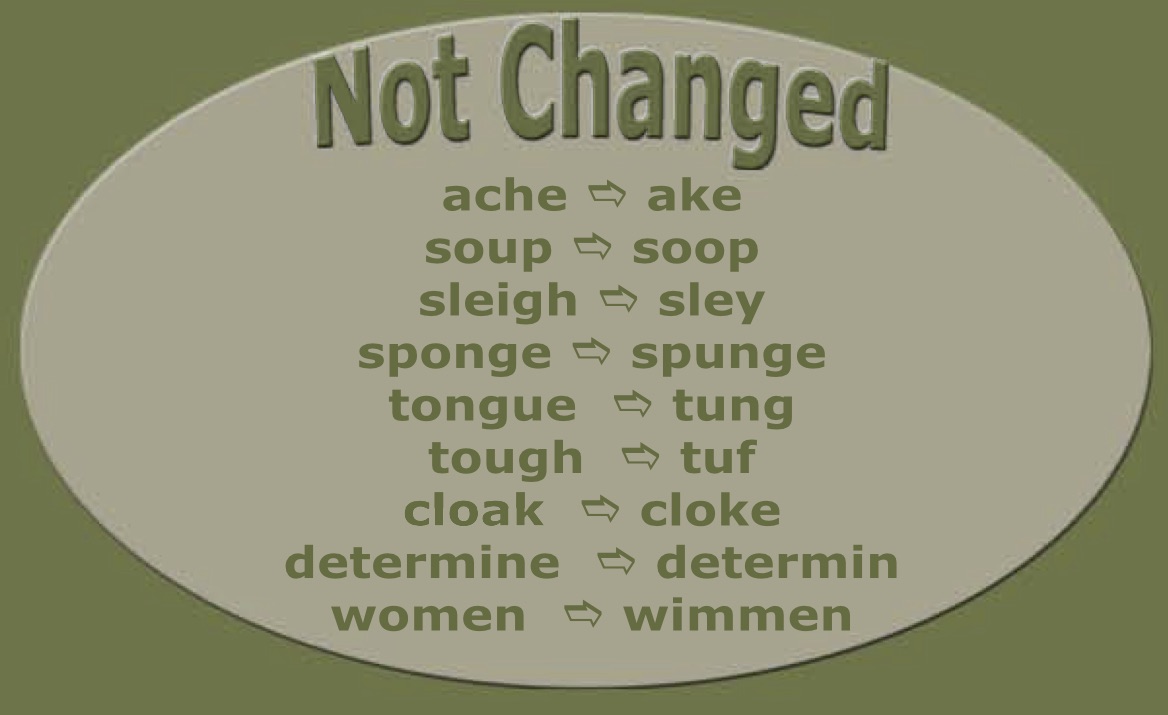

Webster’s greatest influence on English, however, is evident to every person who reads or writes American English – or, perhaps, who struggles with the orthography of intermediate dialects like Canadian and Australian: Webster is primarily responsible for the spelling reforms in American English that for most people distinguish it from British English. His byword was simplicity: why spell it colour when color gives you all the letters you need? Doesn’t jewelry make more sense than jewellery? And since they sound the same, let’s not use both licence with license; the latter can take care of both noun and verb.

Key facts about Noah Webster

HOW DID ENGLISH CHANGE IN AMERICA?

Words such as hickory, opossum, skunk, or succotash are all seamlessly integrated into the fabric of modern English today. Historically, they have two things in common: 1) they are all loanwords from Native American languages, and 2) they all became official English for the first time in Webster’s 1806 dictionary, called A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language. In this work Webster defines many English words for the first time in a dictionary, even though they had been in general or dialectal circulation for decades, or in some cases, even centuries. Spry, for example, had been noted in English and Scottish dialects before, but did not appear in any dictionary. Emphasize, a back-formation from the much earlier emphasis, appears for the first time in the 1806 dictionary, and has no earlier citations than this in the Oxford English Dictionary.

After the appearance of the 1806 dictionary, Webster devoted a good part of the rest of his life to writing the work that made his name the imprimatur for dictionaries in the United States: An American Dictionary of the English Language, first published in 1828. This dictionary, which still has an avid following set the standard for scholarship and precision in English lexicography at the time; a remarkable number of Webster’s definitions remain quite usable today.

Not all the spelling changes Webster advocated for were accepted…

Facts Worth Knowing About the Great American Lexicographer

By Richard Nordquist

During his first career as a schoolteacher at the time of the American Revolution, Webster was concerned that most of his students’ textbooks came from England. So in 1783 he published his own American text, A Grammatical Institute of English Language. The “Blue-Backed Speller,” as it was popularly known, went on to sell nearly 100 million copies over the next century.

Webster subscribed to the biblical account of the origin of language, believing that all languages derived from Chaldee, an Aramaic dialect.

Though he fought for a strong federal government, Webster opposed plans to include a Bill of Rights in the Constitution. “Liberty is never secured with such paper declarations,” he wrote, “nor lost for want of them.”

Even though he himself borrowed shamelessly from Thomas Dilworth’s New Guide to the English Tongue (1740) and Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (1755), Webster fought vigorously to protect his own work from plagiarists. His efforts led to the creation of the first federal copyright laws in 1790.

In 1793 he founded one of New York City’s first daily newspapers, American Minerva, which he edited for four years.

Webster’s Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (1806), a forerunner of An American Dictionary, sparked a “war of the dictionaries” with rival lexicographer Joseph Worchester. But Worchester’s dictionary didn’t stand a chance. Webster’s work, with 5,000 words not included in British dictionaries and with definitions based on the usage of American writers, soon became the recognized authority.

In 1810, he published a booklet on global warming titled “Are Our Winters Getting Warmer?”

Webster was one of the principal founders of Amherst College in Massachusetts.

In 1833 he published his own edition of the bible, updating the vocabulary of the King James version and cleansing it of any words he thought might be considered “offensive, especially for females.”

In 1966, Webster’s restored birthplace and childhood home in West Hartford was reopened as a museum, which you may visit online at the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society. After the tour, you may feel inspired to browse through the original edition of Webster’s American Dictionary of the English Language.