Solon’s Elegies

Listen to the poem in Ancient Greek

From Solon, Elegies — Original Text (ca. 640-560 BCE)

Translation by Douglas Ε. Gerber

Solon speaks of his freeing and returning to Athens a number of citizens who had been enslaved as a result of debt.

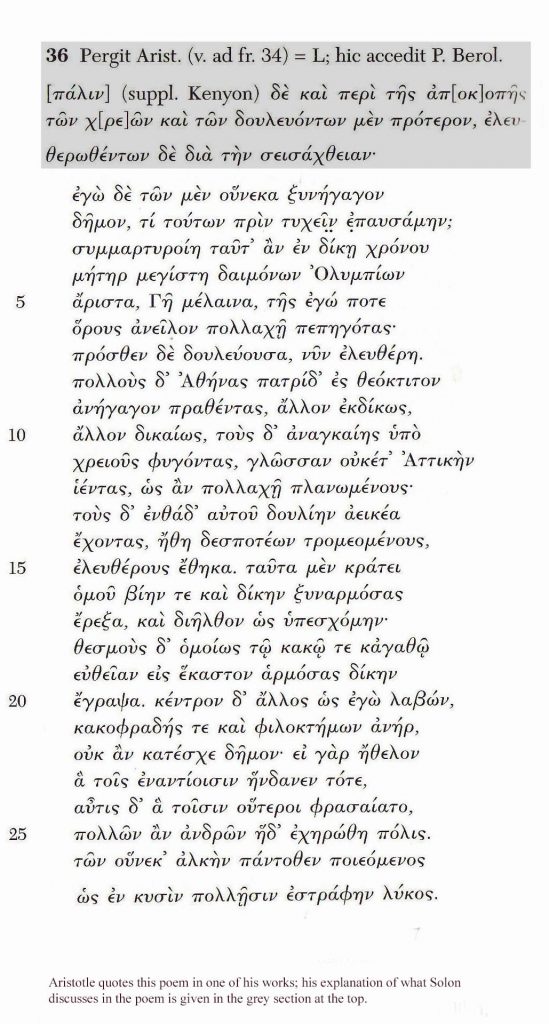

36. Aristotle continues: And again on the cancellation of debts and οn those who were slaves before and were set free by the shaking-off of burdens:1

Before achieving what of the goals for which I brought the people together2 did I stop? Ιn the verdict of time I will have as my best witness the mighty mother of the Olympian gods, dark Earth, whose boundary markers3 fixed in many places I once removed; enslaved before, now she is free. And I brought back to Athens, to their homeland founded by the gods, many who had been sold, one legally another not, and those who had fled under necessity’s constraint, nο longer speaking the Attic tongue, as wanderers far and wide are inclined to do. And those who suffered shameful slavery right here, trembling before the whims of their masters, 1 set free. These things I did by the exercise of my power, blending together force and justice, and 1 persevered to the end as I promised. 1 wrote laws for the lower and upper classes alike, providing a straight legal process for each person. If another had taken up the goad as I did, a man who gave bad counsel and was greedy, he would not have re strained the masses. For if I had been willing to do what then was pleasing to their opponents and in turn whatever the others [i.e., the masses] planned for them, this city would have been bereft of many men. For that reason I set up a defence οn every side and turned about like a wolf among a pack of dogs.

- Α literal translation of seisachtheia. The term was given to Solon’s cancellation of debts and according to Plutarch (Solon 15.2) it was a euphemism actually coined by Solon.

- Precise meaning disputed.

- As a sign of mortgaged land.

Biographical Information

Solon Of Athens (Ca. 640 – Ca. 560 BCE)

Solon was born into an aristocratic Athenian family. His lifetime coincided with a time of bitter social struggles. The rise of trade and an economy based on monetary wealth rather than land-based increased tensions between social classes. Non-wealthy peasant farmers and wage-earners could not compete against the wealthier members of society, sometimes being forced into debt slavery. Violent outbreaks over economic inequality broke out in multiple places. Around the time of Solon’s birth, the small-farm peasants of Megara uprose against the aristocratic landowners, killing all their flocks, and there were violent outbreaks in Miletus. In Megara, one Theagenes led the revolt and the attacks on the flocks of the wealthy, eventually establishing a tyranny there. Lesky notes that the word tyrannos, a loan word from an Asia Minor language that denotes a sole ruler, necessarily contained the germ of the bad sense that the word “tyrant” eventually acquired. However, a number of early Greek tyrants were benign and beneficial to their home cities, serving as patrons of the arts and encouraging the religion of the common people.

In some parts of the Greek world, conflicting parties would appoint arbitrators to settle dsiputes: in Mytilene, Pittacus was chosen to serve as aesymnetes (αισυμνητης −− regulator/ judge/ umpire; president/ manager). Athens appointed Solon a diallaktes (διαλλακτης −− arranger, reconciler) in 594/3 BCE, giving him full powers to arrange a settlement in the city. Solon had to deal with issues such as Athens’ struggle to re-establish her naval power, calls for the abolition of debt and the redistribution of land. He did manage to accomplish the abolition of debt servitude; Solon also reformed the coinage and the system of weights and measures, and reformed the Athenian constitution via his code of laws.Solon describes his political actions in his poetry, and in one long elegy (1 D; Gerber 13) he lays out his philosophy of life. He begins by asking the Muses for the blessings of life, i.e., prosperity and reputation. Following the old moral code of the aristocracy, he desires to do good to his friends and harm to his enemies. Later in 1 D Solon gives examples of the hard struggle humans have in all areas of life, asserting that no one can escape his destiny, which Solon sees as inseparable from the will of the gods. Solon in 1 D distinguishes between two types of prosperity: that which the gods give (good prosperity), and that which comes to someone who has been seduced by evil courses (bad prosperity). People who gain prosperity in this way are subject to bad luck. Those who commit hybris (impious and violent disregard of justice) overstep the boundaries set down for them by the gods, but Dike (Right, Justice) will find them out. For Solon, Zeus is the supreme guarantor of moral law, punishing hybris like the spring gale that cleanses the sky of clouds.

Sources

Lesky, Albin. A History of Greek Literature. Tr. James Willis and Cornelis de Heer. 2nd ed. (1966).

Greek Iambic Poets. Ed. And transl. Douglas E. Gerber. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Lesky, pp. 121-128