Guest post by Julian Walker, Co-Director of the Languages and the First World War project.

The Languages and the First World War project grew from the book Trench Talk, by the military historian Peter Doyle and the linguistics writer Julian Walker, published in 2012. This study of the growth in technical, official and slang vocabulary during and after the conflict gave rise to conversations with military historians and linguists about related phenomena in other languages, and it quickly became apparent that the developments within languages were related to contact between languages. It was decided that the best way to explore these ideas, and to benefit from the surge in interest in the conflict generated by the centenary, was to set up an international conference where the breadth of material could be presented and an international information and contact base could be set up.

The Languages and the First World War project grew from the book Trench Talk, by the military historian Peter Doyle and the linguistics writer Julian Walker, published in 2012. This study of the growth in technical, official and slang vocabulary during and after the conflict gave rise to conversations with military historians and linguists about related phenomena in other languages, and it quickly became apparent that the developments within languages were related to contact between languages. It was decided that the best way to explore these ideas, and to benefit from the surge in interest in the conflict generated by the centenary, was to set up an international conference where the breadth of material could be presented and an international information and contact base could be set up.

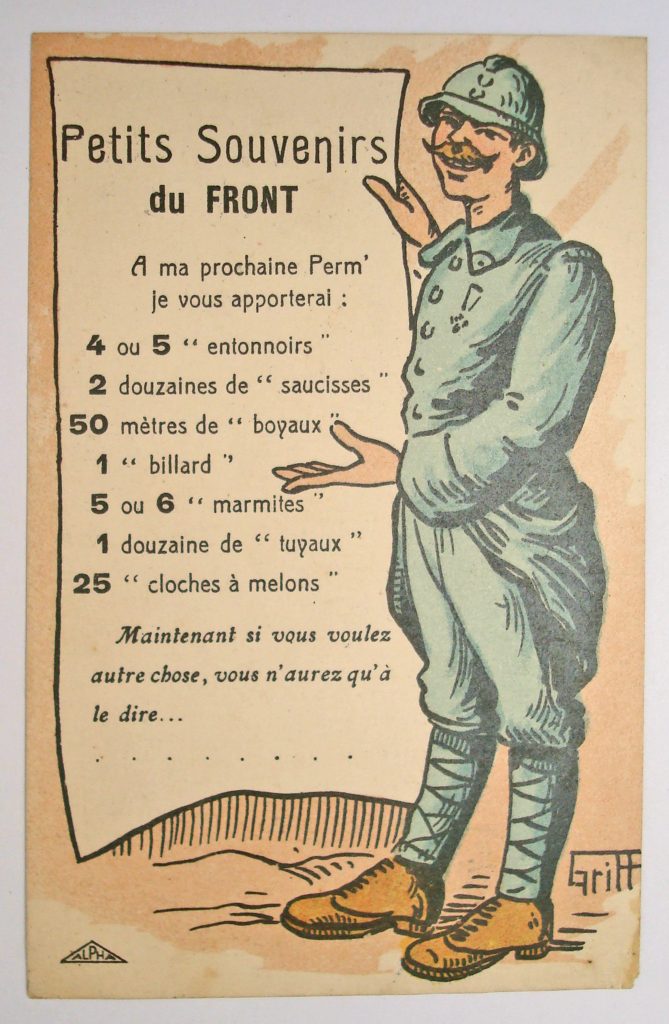

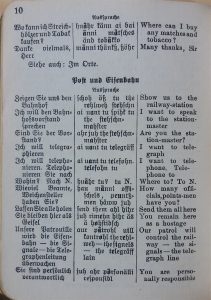

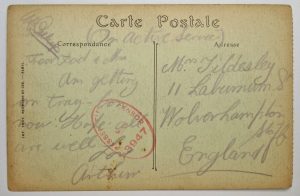

The conference in Antwerp and London in June 2014 saw papers on over 30 topics, including: the contemporary collecting of language; the tension surrounding non-dominant languages within nations, such as Flemish, Welsh, and Maltese; the use of foreign-language phrasebooks by soldiers; the way that the situation of refugees was reported in the press; the correspondences between the slang usages in opposing armies; the comparative use of dialect and standard Italian in soldier’s journals; the language of soldiers’ letters and records; the concept of gendered language during the war; and, in the post-war era, how soldiers’ language was used in fiction; the influence of the war on lexicography; and the various sociolects that the aftermath has produced, to the present.

Multilingual situations provided a number of intriguing studies: how did occupied French people deal with the language of their occupiers; how did soldiers’ French contribute to the sense of nation among Australian veterans; and how did the British Army censors manage the vast correspondence between Indian soldiers in Europe and their families at home?

A blog set up to publicize the conference and to offer example ideas for papers and further study has continued to the present, with guest blogs and studies of linguistic phenomena such as the mythology of slang, documentation of communicability problems within languages because of accent, reticence in soldiers’ correspondence, and the commercial exploitation of slang.

Two volumes of essays, Languages and the First World War: Communicating in a Transnational War and Languages and the First World War: Representation and Memory, have set out a wealth of material, indicative of the ways that language offers a fresh approach to studying the conflict, and how the extended case study of the war offers a way of looking at how language operates under conditions of extreme social stress. The books, published by Palgrave Macmillan, are available in hardcover and as eBooks, and the individual essays can be purchased in digital form.

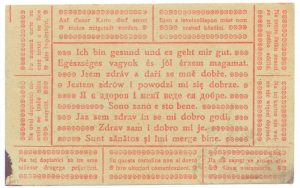

For students and enthusiasts of both language and the history of conflict the subject matter provides some extraordinary examples of how language both directs and reflects the relationship between people in situations of combat, fear, boredom, survival and hierarchy-management. Tamara Scheer’s essay on how the Austro-Hungarian armies managed to maintain lines of communication and correspondence shows an institution which, despite having to use up to twelve official languages, was able to successfully pursue military campaigns. Christophe Declercq’s essay on the linguistic reaction to the arrival of several thousand Belgian refugees in Britain shows how the appearance and gradual disappearance of Flemish in the British press reflected the changing reaction of the host nation to the people fleeing from the war. Richard Fogarty’s essay explores how the use of a particular type of simplified French between officers and Senegalese soldiers in the French army conflicted with France’s colonial mission to spread French values via the language.

The conference planned for the summer of 2018 hopes to both widen the scope of languages and address the question of how language influenced and reflected the ending of the war and its aftermath. Particularly we are interested in material about Turkish, Portuguese, Chinese, Japanese, Russian, Bulgarian, Greek and Arabic; in the linguistic influence of America’s entry into the conflict, particularly how Americans of German or Austrian descent managed, or were indeed used; and how Native American languages were used. In the post-war field there are particular issues surrounding the wording of the Versailles Treaty, commemorative sculptures, and battlefield pilgrimages.

Several subjects remain to be explored: the use of multilingual phrasebooks; corresponding transcriptions of the sounds of the battlefield; comparisons of censorship between nations; comparison of the language of different layers of propaganda; comparison of how resistance to war was treated linguistically in different nations; the nature of soldiers’ post-war silence; and the degree of resurgence in 1939/1941 of the language of the First World War.

What has become apparent is the extraordinary creativity of language during this period of industrialised destruction. How we understand these two polarities is one of the most dynamic aspects of this project. In Britain, in a change from the usual resistance to change in language, the political, academic and self-appointed ‘guardians of language’ establishment were excited about the prospects of new slang and new terminology, and there were few protests about change; there was a certain amount of wrangling as to etymology, which itself indicates a contest of linguistic ownership and control. For the most part people welcomed new terms and introductions of words from French and German; and there were certain groups marked out as social failures for their inability to manage new slang correctly. Meantime among the soldiers at the Front there grew an awareness that soldiers and civilians spoke different languages, that the soldiers’ language both bound them together and separated them from the home they longed to get back to. The disappearance of soldiers’ slang after the war, like the earlier disappearance of refugees’ Flemish, indicates how society adjusted to the changing status of a large but no longer important social group.

The Languages and the First World War blog welcomes guest blog-writers; please send material for consideration to languages.fww@outlook.com