Have you ever learned to read and write from a reader in elementary school? Have you ever published a book under copyright or wondered how we established intellectual property? Have you ever seen the word “color” and wondered why Americans omit the “u?” Whether or not you know, the man whose dictionary was probably a staple of your schooling, Noah Webster, is to be thanked. And in 2018, we are celebrating several milestones, including his 260th birthday, 175 years since his death, and, most notably, the 190th anniversary of An American Dictionary of the English Language.

Just who is Noah Webster?

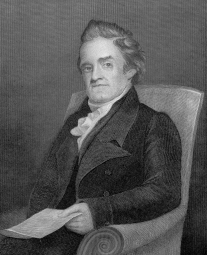

As you may have guessed, Noah Webster is more than a man who published a dictionary. Born October 16th, 1758, in the West Division of Hartford, a British colony, later named West Hartford, Connecticut. Webster was an early proponent of literacy, a member of the House of Representatives, and a force in the abolitionist movement.

Where did the initial idea for the dictionary come from?

Prior to the publication of his dictionary, Webster helped revolutionize how students learned to read and write. Although Noah’s father found it imperative his children be taught in all areas of knowledge, Webster did not always have the best formal schooling. After a lackluster education in an old-fashioned schoolhouse, which caused him to believe teachers to be the “dregs of humanity,” he decided to take knowledge into his own , receiving approval from his parents to be tutored by a local minister and eventually graduating from Yale. From 1783 to 1785, he published three books, a speller, a grammar, and a reader, under the name A Grammatical Institute of the English Language, or the Blue-Back Speller based on the original color of the cover. Similar to textbooks of today, the books were arranged to be done in sequence, so that students with no formal knowledge could learn simple words in the speller all the way to more advanced topics in the reader. Although standard in today’s public schools, for his time this organization was revolutionary.

The Blue-Backed Speller would come to be the spark that led to his dictionary. Always a patriot, Webster believed that a unification of a language was essential to nation building. Although Dr. Johnson’s textbook was still the go-to reference of the day, Webster wanted to create a dictionary that was uniquely American. What many people may not know is that Webster actually wrote two dictionaries; the first, A Compendious Dictionary of the American Language, was published in 1806 in haste as two other authors had already published dictionaries. Although the initial publication was a failure, this did not deter him. Travelling around the world, and running out of money several times, Webster researched word origins and previous dictionaries. In 1828, he released his first set for $20, containing 70,000 words (compared to today’s 470,000!) and was an instant success.

Noah Webster had begun spelling reform with his Blue Backed Speller. He was, even at that time, particularly interested that Americans pronounce and spell words in the American way, not the British way. In his Speller, he separated words by syllable and categorized them by the syllable that received the accent. For instance, in “Words of three syllables, accented on the first” we find: ‘ad jec tive’ and ‘fab u lous.’ In “Words of three syllables, accented on the second” he offers: ‘ac know ledge’ and ‘stu pen dous.’

Webster also pointed out problem words that caused trouble in American English. In Lesson I of Table XXV, Webster criticizes the use of ‘er’ sound at the end of words like ‘follow’ and ‘pillow.’ This tendency he blames on London’s “cockney pronunciation.” In the lesson, Webster admonishes that children should “be taught that w is silent and o retains its proper sound” as in ‘mel low’ and ‘shal low.’

In the Speller, Webster wanted to be sure that American children deviated from standard British pronunciation when possible. He used as an example the words ‘cluster’ and ‘habit’: in British English they are accented as ‘clu-ster’ and ‘ha-bit.’ Webster recommended teaching children that these words should be pronounced as ‘clus-ter’ and ‘hab-it.’ “Let words be divided as they ought to be pronounced,” Webster wrote, “… and the smallest child cannot mistake a just pronunciation.”

In his 1828 dictionary, Webster added words unique to North America, many of which originated from the continent’s Native Americans; for example: ‘skunk,’ ‘squash,’ and ‘lacrosse.’ Webster also identified words that took on special American meaning. ‘Federal,’ ‘constitution,’ and ‘patriot’ were words that hitherto existed but took on new definitions in relation to American history.

Why is it called Merriam-Webster now?

After Webster’s death in 1843, two gentlemen, George and Charles Merriam, were given the publishing rights to the dictionary, initially simply adding new sections but later responsible for revision and additions. The first edition under the new title was published in 1847. Now, you’re also able to find the Collegiate and International editions of the book, and of course their wealth of knowledge is available on the Internet, which we can be sure Webster would have been a proponent of with its ability to disseminate information.

How do we still see Webster’s impact today?

To assess just how much Webster has done for American English, we turned to the Noah Webster House, and asked Jennifer DiCola Matos, the Executive Director.

Noah Webster’s legacy as a founding father of our nation continues to impact us in ways most us would not even consider. For instance, the fact that we grow up with an inherent sense of patriotism – I would credit Webster’s Blue-backed Speller for spreading that sensibility from generation to generation. The American English we use every day and that sense of ‘Americanism’ we share – that’s also Webster’s design. Webster’s goal was to create an American language so that “all persons of every rank, would speak with some degree of precision and uniformity” with the theory that if “…all men are upon a footing and no singularities are accounted vulgar or ridiculous, every man enjoys perfect liberty.” Noah Webster achieved that goal. Certainly, there are still pedants amongst us, but overall we enjoy the freedom to use new words and terms as we like, and as those words become more popular, they often find their way into the Merriam-Webster Dictionary. And Noah Webster would be ok with that, as he said himself: “A living language must keep pace with improvements in knowledge, and with the multiplication of ideas.”

The Noah Webster House (a friend of the museum) is still standing and open to the public. For more information, please visit https://noahwebsterhouse.org/