NML Vice President Greg Nedved sits down with the founders of the Languages and the First World War project. Click here for the full interview.

What is your own language and academic background?

Julian Walker: My first language is English; I studied French and Latin at school, and picked up conversational Spanish later. I can get by in German and Italian. Over the past ten years I’ve worked with the history of the English language, particularly etymology, and have been working on English during the First World War since 2010.

Christophe Declercq: I’m Belgian, so my native language could go either way between Dutch or French, but it’s the former. I’m a translator by education, with English as my second language and Russian my third. I can get by in German, some Spanish and Italian. As an academic I’ve worked on the use of language and translation technology to overcome language barriers and facilitate accessibility during conflict.

What should be the role of a language museum?

JW: Apart from the role of a museum to preserve, particularly since the power of digital communication has increased the spread of a number of forms of English, to the detriment of lesser-used languages, museums have an extraordinary potential to create virtual collections. Sound collections can be stored easily and cheaply, while scans of printed and manuscript material allow a broadened access to material. As language is so central to cultures, language museums can be the collections of so much that could be otherwise ignored or lost.

CD: I could not have phrased it better. A language museum to me is the front end of digital humanities, the ultimate community platform for linguistic data, but presented to the general public, not kept in a vault on an academic server.

How did the Languages and the First World War Project get started?

Languages and the First World War grew from the book Trench Talk by Peter Doyle and Julian Walker. The realization that English slang reached out to other languages led to discussion about the idea of a conference to explore links between languages and developments within languages. The opportunity to hold a conference in Antwerp and London encouraged the multi-lingual potential; setting up a blog allowed us to publicise the ideas for the conference, to explore them further afterwards, and to provide a space for discussion.

What was the most important role of languages in WW1?

It’s very difficult to say that one role was the most important; several aspects are of major interest in sociolinguistic terms.

Codeswitching in various forms – lingua franca, what was frequently termed ‘pidgin’ but could be more clearly described as basic forms of foreign words transposed onto home-language grammar, adoptions of foreign words – was a product of people with a wide range of languages having to communicate. Slang grew and was shared between languages; the technical vocabulary developed enormously; and language served to both link soldiers to civilians and create divisions between these two groups.

What is most surprising about the role of languages in WW1?

Several phenomena can claim this description. Tamara Scheer’s work on the Austro-Hungarian armies’ use of several languages pinpointed the essential pragmatism that emerged – including cases of using an ‘enemy’ language as a lingua franca within units, as this was the only way they could communicate. At the same time, one of the ‘home’ languages within the Austro-Hungarian Empire was seen as of suspect loyalty; and within Germany there were strong moves to remove adopted English vocabulary from German.

The mythology of language too is very important. Three phrases, ‘meat-grinder’, ‘ladies from hell’ and ‘plonk’, are all contentious. ‘Meat-grinder’ is widely supposed to have been used at the time to describe the campaigns of Verdun and the Somme, yet there is no written documentation of this term until much later (not that specifically written documentation has to be the only determinant).

There was a misunderstanding of the German slang Kadaververwertungsgeseelschaft, or ‘carcase-grading factory’, used cynically to describe the grading of German soldiers. Somehow this developed into the idea among Allied soldiers, and then the soldiers’ press, that the German army was boiling down corpses for glycerin and fat. The nearest we have come to ‘meat-grinder’ is a report of the Germans using a ‘sausage-grinder’ as part of this supposed process.

‘Ladies from hell’, supposed to be a German epithet for Scottish and Canadian kilted soldiers, survives only as English reportage; and ‘plonk’, supposed to be British and Allied soldier’s French for vin blanc is not reported as a stand-alone term until ten years after the war. These terms survived (‘meat-grinder’ and ‘plonk’ into common usage), though two of the actually most frequently used slang expressions – napoo and san-fairy-ann – faded away within a couple of years of the Armistice.

How did WW1 influence the English language?

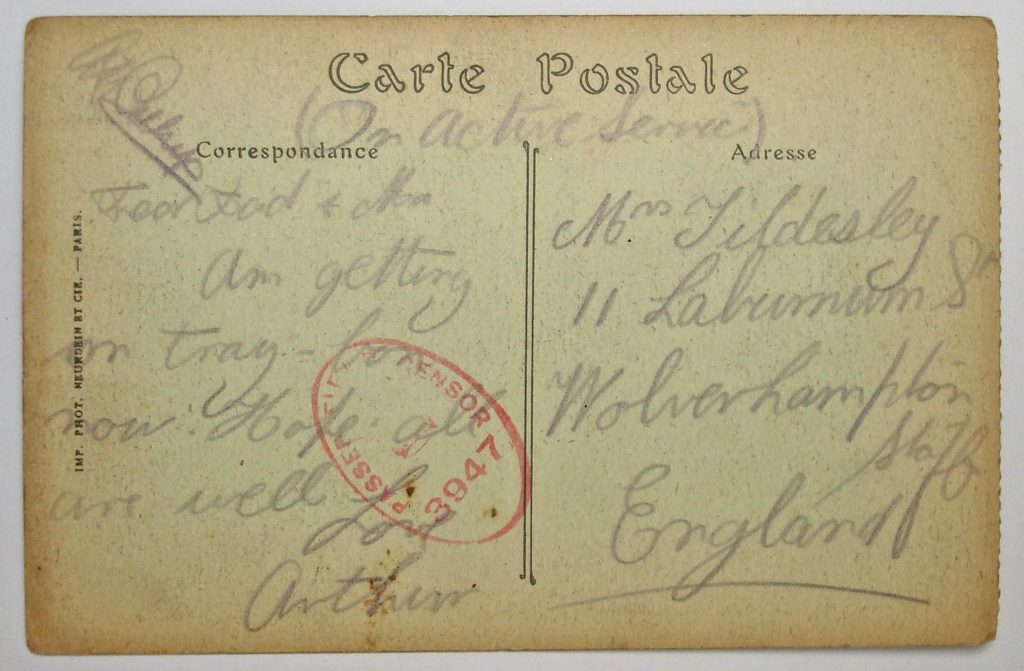

Paul Fussell noted that the war made irony the dominant rhetorical device in English. Cynicism, irony and a wider acceptance of slang and swearing, particularly among the middle classes, became noticeable in English. The massive amount of correspondence flowing between Britain and the Western Front (15,500 bags of mail from Britain to France alone every day) meant that people who would not otherwise have written so much became regular writers, adapting their thoughts to the written language. Self-censorship was a major part of this; it can be equally analysed as writers falling into clichés about health and the weather, or carefully controlling their words to suit their readers.

Also, as the archetypal soldier came to be portrayed as a working-class man from London, there was a spread in the use of cockney expressions and accent; this is documented as pushing out local accents from Scotland particularly.

Which side, the Allies or the Central Powers, held the “language advantage?” in WW1?

Possibly the Central Powers, since they were so well-linked by German. French was widely used throughout Europe as a second language, which would have helped the French and their allies. The British Army had decades of experience in dealing with other languages in Asia, and less so in Africa, but were less well-equipped when it came to European languages – British soldiers particularly expected soldiers of other nations to be able to speak English.

The German occupying authorities in Belgium under General von Bissing used language as a political tool, pointing out that since Flemish was a Germanic language, the Flemings were culturally linked to the Germans. This drove a wedge between the two linguistic cultures of Belgium, the French-speaking Walloons and the Flemish-speaking people of Flanders; linguistic support for Flemish separatism, it was hoped, would lead to closer feelings towards Germany. This was compounded by the fact that French had been the language of status in Belgium pre-war; von Bissing’s decision to make Flemish the language of teaching in the University of Ghent caused major upheavals.

What’s next for Languages and the First World War?

There have naturally been suggestions that we should continue the discussion into the Second World War, which we are considering. Certainly 1939-40 in Britain saw many examples of the revival of many cultural and linguistic tropes from 1914-18. And indeed, for so many nations it can be argued that the First World War created the context for the interwar years which in their turn created the Second World War. In Flanders, for instance, cultural emancipation increased dramatically during the war years, to the lead to popular movements in the 1930s. How these then relate to the Second World War still resonates in Flemish society today. The legacy of the First World War in the Middle East is of an entirely different scale and its complexity resonates today as well. And there is so much unchartered territory in the Far East, or Latin America. And of course more integration of things German.